I’m back from a week-long trip to the Lake District of England, which I can confidently add to my list of favorite places. Ferns poking out of stone walls, established footpaths, water in streams and waterfalls and lakes, public transportation…and countless cups of tea. It seemed as though all of my ideals found some form of expression and I was in absolute heaven.

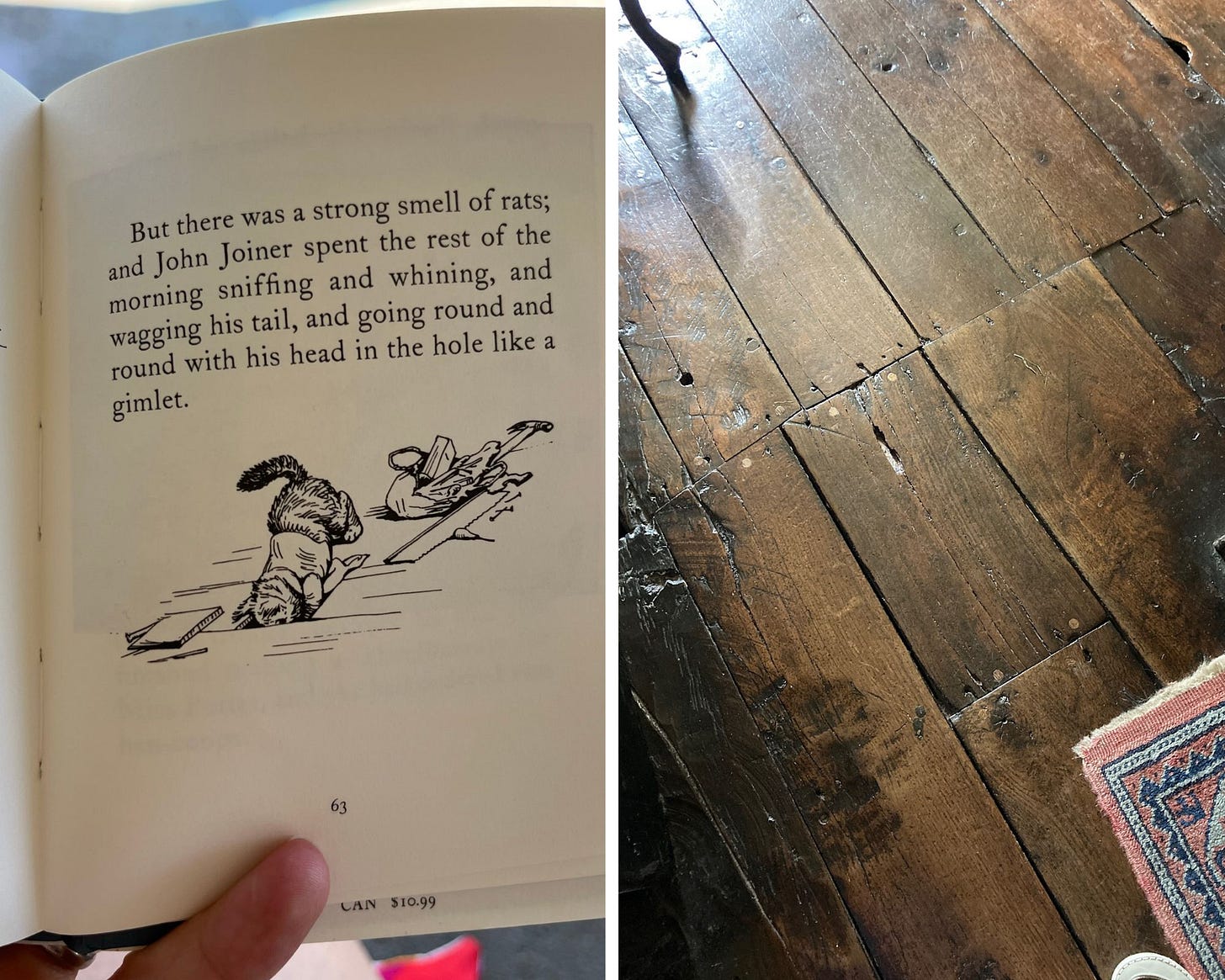

The unforeseen highlight of the trip to the Lake District was walking through the glorious English countryside to arrive at Hill Top, Beatrix Potter’s beloved farm. Purchased by Beatrix Potter in 1905, Hill Top is a 17th-century farmhouse with low-beamed ceilings, snug rooms lined with William Morris floral wallpaper, and a distinctly spicy woodsmoke smell. But I was (shamefully) unaware that Beatrix Potter used Hill Top as the inspiration and backdrop for the illustrations in at least five of her books. Throughout the carefully preserved home, books were unobtrusively opened to illustrations that matched the exact location.

Biographer Margaret Lane writes that “if Beatrix Potter had been a poet, the eight years following the purchase of Hill Top would have been her lyric years.” What is essentially a fantasy world of kittens that wear too-small clothes and frogs who pack picnic baskets is actually situated in the very real world that Potter loved. The most astounding thing of all is that I can still “go inside the book”1 today. It is more magical than Disneyland.

But why is this realization so powerful? Why did I burst into tears as I described the smallest floorboard in the house to Steve?

Several years ago I read an essay by author Walter Wangerin Jr. that continues to inform my litmus test for worthwhile books. In the essay, Wangerin describes a series of covenants that he obeys in order to “shape the tales that shape the children.” His first covenant is with “perceived reality,” or the vital task of depicting what human beings experience in the physical or experiential world with “dead-eye accuracy.” He writes:

No description should come from a writer's false presumption of how the universe works. No writer can live entirely within himself and expect to present a world to his reader which his reader will trust. And once trust is lost in small things it will be lost for the story whole--and that would make for a genuinely lonely profession (which writing is otherwise not).

We, as readers, instinctively and subconsciously know when things are wrong, and so, as Wangerin says, one misstep from the writer risks losing our trust in the entire piece. Why is it so important to retain our trust as readers (aside from the commercial consideration of book sales)? And, put another way, why do I so desperately want the author to be trustworthy?

We know that narrative is innate and central to all human beings. It is fundamental, not only to the preservation of culture, but to the personal development of memory, perspective, agency, and voice. As children, we hear or read stories and then “reconfigure” those words and images to make sense of our reality. (This is why my children spent an entire day recreating their own Wild Cat Island experience in our backyard.) It is as if a story comes into us and becomes a part of us and all of our relationships. I believe that this union with a text carries with it a degree of tender vulnerability: we are trying to sort out the world and stories can be a help or a hindrance. They become a part of us and we cannot walk away unchanged. 2

Even as an adult, I use narrative to make sense of my reality. If I consist of both the stories I consume and the stories I tell, it is necessary for the authors I read to be, as Wangerin says, committed to the self-negating practice of truth-telling:

…I must practice the hard, the sometimes scary exercise of resisting pre-judging those I meet; of admitting that I do not know, and every human before me is a mystery, and I am a stranger in a strange land.

So in order to "get it right," I watch for the truth--not with the truth, as if it were a donkey's tail to pin on the persons I will write about. And I watch with "sympathy."

When I saw Beatrix Potter’s Hill Top and recognized the spaces that were as familiar in my mind as my own home, I was overwhelmed by the feeling that these tales (which had infiltrated my childhood and continue to impact my relationships today) are true. As such, they are safe to be a part of me. Beatrix Potter watched Hill Top with a sympathy that sprang from her own deep affection. She translated that sympathy into her stories and illustrations. In doing so, she established a line of trust that extends down to me over a century later.

A favorite read from July

Elizabeth Strout’s capacity to convey characters as people bearing full expressions of their experiences and choices is a talent that keeps me coming back for more (even when the stories are hard). Lucy by the Sea is a gentle and profound reminder that reaching the final decades of life doesn’t mean that one is finished, but rather that one is still constantly being formed by relationships…the old, established ones, and the new, surprising ones, too.

Aligned with the notion of truth-telling, Strout captures the confusion and isolation of the early weeks of the pandemic, as well as how behaviors changed almost imperceptibly as new information surfaced, was parsed, and then applied. For example, Lucy experiences the mental fog of weeks of lockdown. She begins to notice how people wear masks (below the nose, under the chin, not at all), and then automatically categorizes people into political or ideological camps - a subconscious activity that occupies a tremendous amount of her brain. Strout doesn’t treat the pandemic as an inconvenient blip, but rather as a seismic shift in how we relate to our world.

Thanks to my most fabulous niece for this realization!

The ideas in this paragraph stem from two excellent speakers at the CMI Centenary Conference which we attended in Ambleside, England. Dr. Carroll Smith discussed the centrality of narrative to all human development. Dr. Jack Beckman applied Ricoeur’s theory of narrative (prefiguring, configuring, reconfiguring) to Charlotte Mason’s educational principle of narration, and posited that all narration is the original story “made into the image of the child” - an idea that will impact how I listen and respond to my own children’s narrations.

This was such a lovely dive into memories and feelings of childhood. Recently Bug has gotten into Frog and Toad. While staying with a friend of mine/Auntie he insisted they make a “to-do” list of all the activities they should do together. She was so touched as Frog and Toad is one of her all time favorite childhood books. We all need more of this. 💚

How wonderful to have this beautiful recounting of our experiences! Thank you.